Published in 2A Magazine Issue #45 – Summer 2020

“After some 500 years of a relationship that has swung from partnership to domination, from mutual respect and cooperation to paternalism and attempted assimilation, Canada must now work out fair and lasting terms of coexistence with Aboriginal people.” :

The year 2017 witnessed a full calendar of commemorative events across Canada dedicated to honoring 150 years of the adoption of the British North America Act of 1867 and Canadian confederation. However, the celebratory nature of this achievement was often unwelcomed and challenged by many Indigenous, First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples who have suffered from a legacy of attempted “cultural genocide by their European colonizers and successive governments of Canada over the past 500 years.

One unique form of critique came as an exhibition of paintings, drawings, and sculptural works in dialogue with historical artefacts and art works borrowed from museum and private collections from across the country. Barbara Fischer of the Art Museum at University of Toronto invited Kent Monkman to participate in telling a very different story to the image of peace, generosity, inclusivity, and compassion that Canadians like to promulgate about themselves. Of Cree descent, Monkman’s self-curated, solo exhibition provides, in his own words, a counternarrative to all the celebration through the lens of First Nations’ displacement and resilience.

Juxtaposed with excerpts from the 1996, Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Canada’s Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and the 2015 Report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on the Indian Residential School System, this paper attempts to demonstrate how Kent Monkman’s unique artistic style illustrates the clashing of fundamentally disparate cosmologies that ensured the inevitability of a disastrous relationship for Indigenous peoples with their originally welcomed European visitors. A Euro-centric cosmology founded on the precepts of Christian evangelization, jurisprudence associated with the rights of ownership and private property, and colonial exploitation came into direct conflict with an Indigenous cosmology founded on an understanding of the natural world as sacred, a more considered stewardship of resources, and the notion of fluid boundaries between nation territories where the concept of ownership was inconceivable.

Kent Monkman has been influenced by great European masters such as Rubens, Goya, Caravaggio, Picasso, but in particular by the 19th century North American romantic landscape tradition of artists such as GermanAmerican Albert Bierstadt. By using the same artistic style for his paintings, Monkman draws us into his own pristine landscapes as a way to reclaim them, and upon closer examination, to disrupt any of our pre-conceived notions of idealized Indigenous life and the emotional responses which they evoke with details that introduce a very different, counter narrative.

Juxtaposed against an idealized Canadian landscape, early settlers, drawn by the lucrative fur trade to satisfy the European fashion for beaver garments, are seen here in (Fig. 1) brutally slaughtering one of Canada’s most iconic native creatures while an Indigenous “mother” in the role of Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Kent’s genderfluid, time-travelling, supernatural alter ego, who serves as the narrator throughout Shame and Prejudice, fearfully cowers behind a tree with her “infants”, a helpless witness to the frenzied carnage unfolding before her. The anthropomorphised beavers, some of which can be seen begging for mercy, could be stand-ins for Indigenous people…according to Monkman.

The Commission document acknowledges that during the 1800’s, the relationship between the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people began to tilt on its foundation of mutual respect and equality. The number of settlers was swelling and so was their power. As they dominated the land, so they came to dominate its original inhabitants. They gained power as a result of four changes that were transforming the country:

- The population mix was shifting to favour the settlers. Immigration continued to add to their numbers, while poverty and disease continued to diminish Aboriginal nations. By 1812, immigrants outnumbered indigenous people in Upper Canada by a factor of ten to one.

- The fur trade was dying and with it the old economic partnership between traders and trappers. The new economy was based upon timber, minerals, and agriculture. It needed land not labour from Aboriginal people who began to be seen as impediments to progress instead of valued partners.

- Colonial governments in Upper and Lower Canada no longer needed Aboriginal nations as military allies. The British had defeated all competitors north of the 49th parallel. South of it, the United States had fought for self-government and won. The continent was at peace.

- An ideology proclaiming European superiority over all other peoples of the earth was taking hold. It provided a rationale for policies of domination and assimilation, which slowly replaced partnership in the North American colonies. These policies increased in numbers and bitter effect on Aboriginal people over many years and several generations.”

“Ironically, the transformation from respectful coexistence to domination by non-Aboriginal laws and institutions began with the main instruments of the partnership: the treaties and the Royal Proclamation of 1763. These documents offered Aboriginal people not only peace and friendship, respect and rough equality, but also ‘protection Protection was the leading edge of domination. At first, it meant preservation of Aboriginal lands and cultural integrity from encroachment by settlers. Later, it meant’assistance a code word implying encouragement to stop being Aboriginal and merge into the settler society. Protection took the form of compulsory education, economic adjustment programs, social and political control by federal agents, and much more. These policies, combined with missionary efforts to civilize and convert Indigenous people, tore wide holes in Aboriginal cultures, autonomy and feelings of self-worth.”

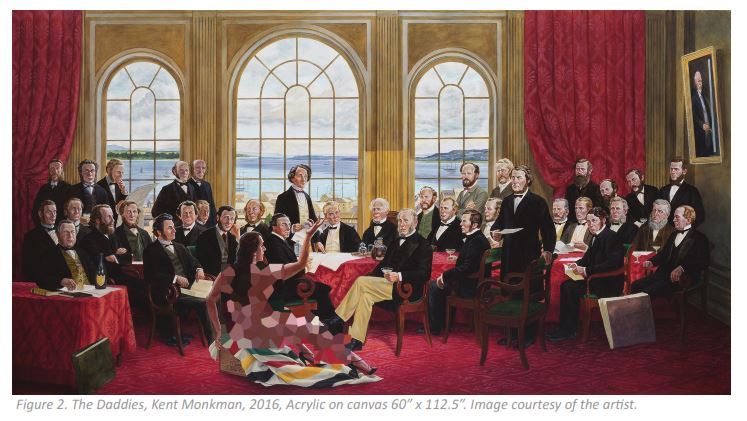

“Confederation, declared in 1867, was a new partnership between English and French colonists to manage lands and resources north of the 49th parallel It was negotiated without reference to Aboriginal nations, the first partners of both the French and the English. Indeed, newly elected Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, announced that “it would be his government’s goal to do away with the tribal system, and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion.”

In (Fig. 2), Miss Chief Eagle Testickle situates herself on the vacant stool found in the original 1884 painting by Robert Harris, as both an object of desire and one that represents the omission of First Nations as part of the new confederation. All eyes are on her as the scotch and champagne flow freely…referencing that these gatherings were often characterized by drunkenness. Two spirited persons were embraced by Indigenous peoples as having special gifts and it was only under the Euro-Christian influence that two spirited persons were deemed to be deviant and came under persecution.

“The 1867 British North America Act, young Canada’s new constitution, made “Indians and lands reserved for the Indians”, a subject for government regulation, like mines or roads. Parliament took on the job with vigour passing laws to replace traditional Aboriginal

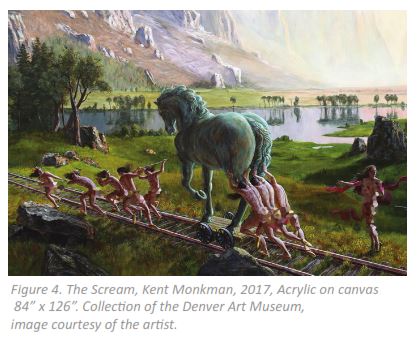

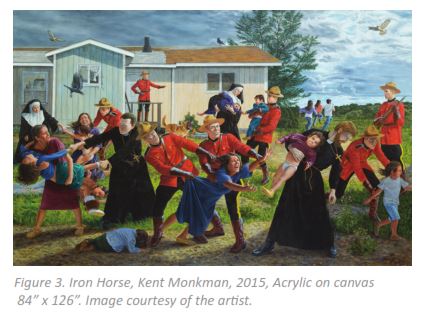

governments with band councils with insignificant powers, taking control of valuable resources located on reserves, taking charge of reserve finances, imposing an unfamiliar system of land tenure and applying nonAboriginal concepts of marriage and parenting.” Like the Trojan Horse, the tale that speaks to the subterfuge that the Greeks used to enter the independent city of Troy and win the war, the railroads were the means by which the new country connected itself from coast to coast, allowing for the rapid and pervasive colonization of the west, the decimation of the Plains Nations major source of food, the bison, and the further displacement and subjugation of Indigenous peoples throughout Canada. (Fig. 3)

In the similarly thematic painting The Scream, (Fig.4) Monkman employs the violence of Peter Paul Rubens painting, Massacre of the Innocents, 1636-38 (Alte Pinakothek), to capture the violence inherent in the legacy of the Residential School System that sought to separate Indigenous children from their parents “..in order to minimize and weaken family ties and cultural linkages, and to indoctrinate children into a new culture-the culture of the legally dominant EuroChristian Canadian society…”. Roman Catholic nuns and priests identified by their iconic vestments along with Canadian Mounties who embody Canada as an iconic symbol of national government and law keeping are seen here forcibly removing children from their parents who live in squalid conditions on a reservation. Some children in the background are seen attempting to run away, a reference to the many children who died trying to find their way home over hundreds of miles. From the 1880’s to as recently as 1996, Indigenous families were subjected to this shameful policy. In government

sponsored residential schools set-up and run by Roman Catholic, Methodist, and Anglican Dioceses, children often suffered emotional, physical, and sexual abuse at the hands of their caregivers and died in numbers that would be unacceptable in any other school system in Canada or anywhere else in the world.”

Displaced physically, forced into marginal lands that could not support their traditional ways of life, many “Status Indians” who live on reservations experience boiled water advisories, substances abuse, broken families, and significantly higher than national average suicide rates, painful reminders of this horrific legacy. Only through the courage of survivors was their story recently brought to the attention of Canadians. And although “The Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission represents an important first step in identifying the systematic subjugation of the truth regarding Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples and our attempt at redressing that legacy, it will likely take several more generations before full healing and reconciliation can be achieved.

“To bring about this fundamental change, Canadians need to understand that Aboriginal peoples are nations. That is, they are political and cultural groups with values and lifeways distinct from those of other Canadians. They lived as nations, highly centralized, loosely federated, or small and clan-based for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. As nations, they forged trade and military alliances among themselves and with the new arrivals. To this day, Aboriginal people’s sense of confidence and well-being as individuals remains tied to the strength of their nations. Only as members of restored nations can they reach their potential in the twenty-first century.”