The ecology-landscape-design rubric in the Arab World

Published in 2A Magazine Issue #15&16 Autumn 2010 Winter 2011

Jala Makhzoumi

Jala Makhzoumi is professor of landscape architecture, the American University of Beirut. She studied architecture at Baghdad University, received a Masters of Environmental Design from Yale University and a PhD in Landscape Architecture from Sheffield University. She pioneers the practice of ecological landscape design in Iraq, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria and the Gulf through projects in nature conservation and rural development, sustainable urban greening and post-war recovery. Her publications include Ecological Landscape Design and Planning. The Mediterranean context, coauthor Gloria Pungetti (London, EF & N Spon, 1999). Jala was member of the UN-HABITAT Higher Advisory Council for the Reconstruction of Iraq, editorial board member for Landscape and Urban Planning, and continues to serve as honorary fellow of the Cambridge Centre for Landscape and People, UK.

The ecology-landscape-design rubric in the Arab World

I first became aware of landscape design when studying architecture. My conception then was informed by the two contrasting: rural hinterlands of palm orchards; a modernizing city centre. The landscape of palm orchards was ordered, defined by tall tree trunks and water channels, layered with patterns of light that filter through high canopies. The space was limitless yet enclosed, flowing and cool. The colors and scents change from one season to another, palms maturing imperceptibly year after year, the landscape itself unchanged, timeless. The urban landscape in contrast was changing, the landscape of wide streets and roundabout, concrete and glass buildings that tower over fragments of the traditional urban fabric. The urban landscape I soon realized was not half as glamorous as the contemporary architecture claimed to be. The generic design of these spaces was invariably of expanses of lawn and flowering borders that remained unchanged throughout the year, struggling to endure infernal summers. Transporting modern landscapes from western, temperate climates into hot arid ones continues to prevail in many Arab cities (Figure 1).

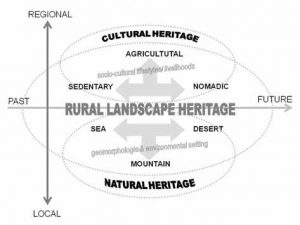

The challenge as I then saw it was to capture the uniqueness of the palm orchard and adapt it to those desolate urban spaces, to develop a landscape vocabulary that was not ‘copied’ or ‘transported’ but that responded to local environmental limitations. Accepting the importance of climate is a key determinant in landscape design, my earliest attempts to meet the challenge followed the path of energy efficient landscape design and site planning (1) . Climate, I eventually realized, was only one determinant. I learnt from ecology, a key influence in my thinking since, that landscapes are shaped through interacting evolutionary processes (landform, geology, hydrology and climate) and that people similarly interact with and shape natural settings to suit their needs for livelihood and habitation. The outcome, the cultural landscape, can be seen in pre-modern urban and traditional rural settings in the Middle East. I found in traditional cultural landscapes guidance and inspiration towards landscape design concepts that are climatically efficient, ecologically sound and aesthetically in harmony with the character of place and region (2) (Figure 2).

- Researching the shading geometry of trees and palms, pergolas and trellises, measuring the reduction in heat gain of outdoor and indoor temperatures resulting from plant shading, I arrived at a landscape design vocabulary that had the potential to improve building site microclimate and reduce building cooling energy requirements (Makhzoumi, 1983; Makhzoumi and Jaff, 1987).

- In Iraq as in the rest of the Middle East, examples abound of cultural landscapes of villages and towns, agricultural and pastoral lands that result from human-environment co-evolution over long time spans. Traditional cultural landscapes are environmentally and ecologically sustainable. Their distinctiveness is integral to the character of place just as they themselves are a natural and cultural heritage of the region (see Makhzoumi and Hassan, 1988; Makhzoumi, 1988; Makhzoumi 1997).

Figure 1 Green spaces in the Middle East are predominantly traffic related or remnant spaces surrounding high rise buildings. The prevailing landscape design favoring lawns and ornamental planting, like the architecture, is transported with disregard to climate and local ecology and the character of place.

In the years that followed I shifted positions between professional practice, teaching and research. Knowledge gained from research informed and expanded my design practice just as creative design thinking helped me conceptualize the discourse on landscape. The outcome is ‘ecological landscape design’, a paradigm that aspires to create places that are in harmony with nature and meaningful to the people that inhabit them. And because the essence of the paradigm lies in the rubric formed by ecology- landscape design, I shall define each as I came to understand them.

Ecology is the science of nature and the basis for understanding natural systems that support life on earth and sustain the biosphere we inhabit. Landscape ecology, a young branch of ecology, adopts a holistic, systems approach to appreciate the complexity of the interrelationships between humans and their open and built-up landscapes (3) . Ecology guides conservation scientists, regional planners, local authorities and more recently landscape architects guiding them towards sustainable management of natural and cultural resources.

The English word landscape implies at once a product, a tangible piece of land with its system of living, non-living and human components, and production, the process of shaping the landscape together with all associated perceptions and valuations. The historical evolution of the English word reflects the complexity and layered meanings of landscape, and explains the difficulty of finding a corresponding word in Arabic (4) Above all, landscape is more than a word, it is an complex ‘idea’ a way of reading and conceptualizing our surroundings that is dynamic spatiality, because landscapes are contiguous from the local to the regional and global, and temporality, because landscapes are forever evolving, flowing from past to present, projecting into the future.

Design in architecture, landscape and urban design is a creative, problem-solving activity that accommodates needs and aspirations (of people, institutions, local authorities) by matching them to available resources (human, cultural and natural) in the process of shaping places of work, habitation and recreation.

The theoretical framework of the ecological landscape design paradigm (5) draws on the holistic, system-thinking principles of landscape ecology, the discursive framework of landscape and the creative, problem-solving skills of design to engender landscape narratives that are sustainable ecologically, responsive to the character of place/region and inclusive of local cultures. The efficacy of the paradigm lies in its ability to serve as an investigative framework that can provide a dynamic reading of people and place but also as a holistic medium for writing landscapes that are sustainable environmentally, socially and culturally.

- Holistic implies that the total (landscape/ecosystem) incorporating socio-economic, ecological and environmental components, is more than the sum of each of these components, and that failing to consider the total is detrimental to human wellbeing and the health of the natural world.

- The Germanic-Dutch origin of the English word ‘landscape’ meaning ‘region’ or ‘tract’, was eventually superseded by a painterly, visual meaning. Despite more recent interpretations from cultural geography, anthropology and landscape ecology, the visual meaning continues to dominate in the general use of the word and most Arabic translations of ‘landscape’ (see Makhzoumi 2002)

- The Ecological Landscape Design paradigm was proposed in my doctorate research at Sheffield University in 1996, developed later in Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 1999

Figure 3. Landscape concepts for the development of the historic town of Kadhimiya (source: Dewan Architects and Engineers, 2009)

The practice of ecological landscape design is in itself a challenge. The absence of an Arabic word for landscape results in a borrowing of cultural interpretations from the West (6). The outcome not only limits the professional role, reducing it to superficial ‘beautification’, but in addition, sidesteps the diversity and wealth of the regional landscape heritage. In contrast, ecological landscape design, whether as an intellectual discourse or as a framework for design and planning, has the potential to broadens the professional scope by responding to a diversity of scales (inner city, metropolitan, regional), a wide range of agendas (nature/biodiversity conservation, landscape heritage, ecological tourism, rural development) and a varied locations (urban, rural). To elaborate further, I will draw on two recent applications that enabled me to test the methodology in two different settings.

In Kadhimiya town, Baghdad, Iraq (7) the challenge was to green the thousand-year historic, densely built urban core. The landscape master plan aim was to rehabilitate open spaces to better serve residents and pilgrims to the shrine, to improve the urban microclimate and to upgrade and enhance the quality of urban life. The multi-scalar, hierarchical approach of landscape ecology provides a dynamic spatial reading of Kadhimiya configured as a continuum with small neighborhood spaces at one end and at the other, the historic city in its entirety. At the larger scale, landscape strategies prioritize on re-connecting spatially, perceptually and ecologically the historic town with the Tigris River, the larger context from which it had been severed. At the local scale, the strategies enhance the quality of urban spaces through non-conventional, energy efficient greening concepts, for example roof and vertical gardens, green portals and green edges and peripheries)( Figure 3). The complementarity of small-scale and large-scale strategies enables landscape to serve as the unifying fabric, contextualizing new development and historic shrine and neighborhoods.

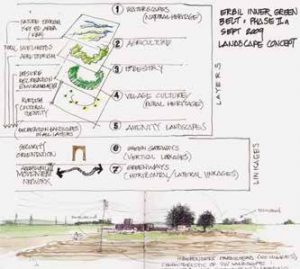

The Erbil Green Belt project (8) is another application of ecological landscape design. A holistic reading of the existing green belt landscape (2 km wide, 14 km radius) inspired innovative, environmentally and ecologically sustainable concepts that were adopted by the interdisciplinary master plan team. The landscape is predominantly rural, with rain fed arable farming and pasture lands, villages and a complex network of seasonal water courses. Steering away from conventional shelterbelt planning that commence with the indiscriminate appropriation of agricultural lands and proceeds to establishing uniform shelterbelt planting, the ecological landscape approach conceptualizes the green

- (see Makhzoumi, “looking West, looking East: the challenge for landscape architecture in the Middle East and North Africa, IFLA Dubai, 2008)

- Competition for Developing the Area Sorrounding the Holy Shrines in Kadhimiya, Iraq. In association with Dewan Architects and Engineers. The team was awarded first place by Baghdad Municipality in March 2010.

- Erbil Inner Green Belt Project, Iraq. In association with Khatib and Alami Consolidated Engineers

Figure 4. Landscape concepts for the Erbil Green Belt project (Khatib and Alami Consolidated Engineers, 2010)

belt as a platform for celebrating Kurdish rural heritage, a multifunctional landscape that is at once productive (agriculture, farms and orchards) and recreational (parkland, greenways, sports and amenity services). While the priority is to contain suburban spill and improve urban microclimate, the ecological approach is broad and dynamic, prioritizing on biodiversity conservation. Connectedness and linkages was a key landscape objective for networking green spaces. While two of the larger watercourses, were conceptualized as greenways that will harbor the local wildlife and serve as linear parks, minor watercourses were integrated into the landscape of the Green Belt parks. In total, the network of greenways and ecological corridors secure the ecological continuity with the Kurdish foothills, anchor the expanding city into its rural hinterland and provide future landscapes that are inspired by the hilly landscapes of Iraq’s northern region (Figure 4)

The quest for a discourse on landscape in the Middle East continues to be at the centre of my professional and academic life. And while the beauty and diversity of the regional landscape, at once a natural and cultural heritage, are a source of inspiration, intellectually I am fascinated by the idea of landscape as the arena within which communities negotiate how they relate to nature and environment, their collective identities, their past and future (9). In ecological landscape design I have found a path for acknowledging the landscape heritage and protecting natural resources as a basis for human wellbeing.

References

Makhzoumi, J. (2011) “Is rural heritage relevant in an urbanizing Mashreq? Exploring the discourse of landscape heritage in Lebanon”. In I Maffi and R Daher (eds) Practices of Patrimonialization in the Arab World: Positioning the Material Past in Contemporary Societies. I.B. Tauris (in progress)

Makhzoumi, J. (2008) “looking West, looking East: the challenge for landscape architecture in the Middle East and North Africa”, invited presentation, International Federation of Landscape Architects Symposium, Dubai.

Makhzoumi, J. (2002) “Landscape in the Middle East: An inquiry”, Landscape Research Vol. 27, No.3, pp. 213-228

Makhzoumi, J. and Pungetti, G. (1999) Ecological Landscape Design and Planning. The Mediterranean context, E & FN Spon, London.

Makhzoumi, J. (1997) “The changing role of rural landscapes: olive and carob multi-use tree plantations in the semiarid Mediterranean” Landscape and Urban Planning, Volume 37, pp. 115-122.

Makhzoumi, J (1988) ‘An ecological context for the design of human settlements’. Iraqi Scientific Council, Journal of the Building Research Centre Vol 7, no. 1 (Arabic)

Makhzoumi, J., Hasan, A., (1988) “Ecologically responsive settlements: A case study of Ana in the Western Iraqi Region”. In: de O. Fernandes and S. Yannas (eds) Energy and Building for Temperate Climates: A Mediterranean Regional Approach. Pergamon Press, London. pp. 205-212;

Makhzoumi, J and Jaff, A. (1987) “Applications of trellises in retrofitting buildings in hot-arid climates”. International Building Energy Management Conference, proceedings, Lausanne, Switzerland. pp. 460-466.

Makhzoumi, J. (1983) “Low energy alternatives for site planning through the use of trees in a hot arid climate”. In S. Yannas and A. Bowen (eds) Passive and Low Energy Architecture. Pergamon Press, Oxford. pp. 499-505

The European Landscape Convention is the first international initiative of scale to recognize the role of ‘landscape’ as essential to people’s quality of life, to human fulfillment and the consolidation of the European identity (http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/cultureheritage/heritage/landscape/default_en.asp)