Creating a Sense of the Sacred: The Palliative Care Center at the University Hospital in Göttingen, Germany

Susanne Siepl-Coates

Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas

Published in 2A Magazine Issue #12 – Autumn 2009

Professor Susanne Siepl-Coates is a member of the architecture faculty at Kansas State University. She earned her Master of Architecture (M. Arch) degree as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of California, Berkeley (1982) where she studied and subsequently worked with the internationally renowned architect and educator Christopher Alexander. Her research and teaching focus on the exploration of the relationships between the built environment and human health and well-being.

[email protected]

When it has been established that a severely ill person no longer benefits from major medical interventions, palliative end-of-life care may be proposed. Along with a shift in treatment, a move from the clinical setting of the typical hospital to an environment that is sensitive to the circumstances of the patient’s suffering and respectful of the patient’s impending transition may be appropriate. For an architect of such end-of-life settings questions arise: how can the physical environment contribute to counteracting typical feelings such as fear and isolation? How can architecture support patients, their families and care givers by giving expression to symbolic and spiritual dimensions of dying while not disregarding the functional aspects of palliative care. Can architecture contribute to establishing death as a celebrated part of life, similar to birth? Is it possible to create a sense of the sacred in the everyday life of a palliative care unit?

The Palliative Care Center at the University Hospital in Göttingen, Germany, designed by the Göttingen firm bmp architekten and opened in January 2007, can make significant contributions to answering these questions and to advancing the discussion about what the architecture of palliative care, perhaps even health care altogether, should be in the future.

Patients on this ward are extremely ill, often close to death, and typically suffering from extreme physical pain and other debilitating symptoms. The goal of palliative medicine is to reduce human suffering and to stabilize, and possibly improve, the quality of life of the patients during the last weeks and days of life. Pain reduction and symptom control are achieved through a holistic care model that includes medical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions.

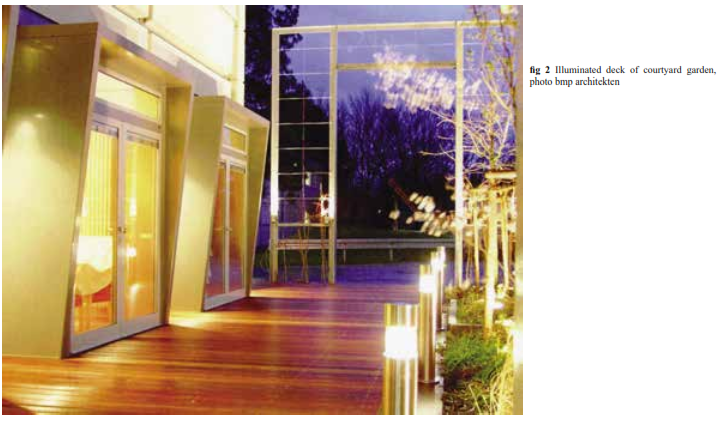

In designing the Göttingen unit, the architect worked closely with the staff psychologist to give architectural expression to this holistic model of care. Taking its clue from the word ‘pallium’, Latin for ‘coat’ or ‘cloak’, trellised climbing plants provide a green protective layer on the exterior of the palliative ward shielding patient rooms, wooden decks and adjacent garden rooms.

Careful detailing facilitates ease and comfort of use and assists patients in their struggle to adapt to the changes in life circumstance. Furnishings are selected with regard to materiality and color in order to support the patient’s physical and psychological well-being. Along a single-loaded corridor the glazed spaces between the structural supports have been developed into alcoves, allowing either for a temporary retreat from activity or for quiet conversation between patients and visitors, while offering views into an exterior courtyard garden.

Both inside and out, materials and colors generate a sense of subtle warmth and create an ambiance that offers a variety of activities and moods: outward views and inner reflection, stimulation and relaxation, calmness and movement, communication and silence, activity and withdrawal. By doing so, psycho-social and spiritual aspects of life are moved into the foreground, made possible by the spatial organization of the ward and emphasized through innovative and thoughtful details.

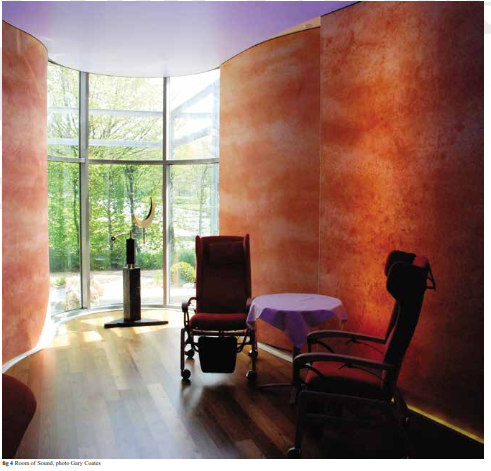

Two spaces were given particular attention. The Room of Sound is intended as ‘a world apart’ and highly contemplative in nature. A narrow band of light separates the acacia wood floor surface from the walls. The walls themselves are made of soft batik-dyed orange fabric and curve gently, perhaps reminiscent of a womb. The suspended ceiling plane is made of joint-less stretched film upon which moving clouds and the daylight spectrum of colors can be projected.

Given its intention to provide an experience of sound, several flat loudspeakers hidden behind the wall fabric can create soothing soundscapes which further enhance the wide range of possible light moods. Curved glass panes offer views of a small meditative garden where the gentle flow of spring water flows from a rock into simple reflective water basin. A small sculpture inside the window invites silent meditation.

Distinguishing itself radically from institutional bathrooms, the Bathing Room focuses on feeling and seeing. The rectangular volume of the space is softened

by an inner curved wall, which elegantly hides cabinets and a sink while providing a glow of indirect lighting for the space.

Reminiscent of a wellness spa rather than the ward of a hospital, the bath contains a tub that features water jets and small light sources incorporated into its inner lining, a ‘rain shower’ as well as a infrared lights to dry off quickly without the use of towels. On the wall across from the tub is a large-scale screen upon which a variety of soothing movies, typically of water or landscape scenes, can be projected.

To further enhance the experience of this bathing event, the ceiling is dotted with

tiny sparkling star-like lights, the color of which can be adjusted to the patient’s wishes. There is also a stereo to support the mood with appropriate music as well as the possibility for aromatherapy. Feeling via the skin, such as experiencing water on one’s body, is not only a joyful sense perception but also a sensation that can be experienced up until the very end.

Focusing on life rather than death, this facility not only affords the best quality of life possible under the circumstances but also provides an instructive example of how the experience of everyday activities, which as healthy persons often take for granted, can potentially create a sacred atmosphere for the transition into death.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Dirk Eggebrecht, Dipl. Psych., staff member of the Palliative Care Center at Universitätsmedizin Göttingen; and Michael Timm, Dipl. Ing., of bmp architekten, both of whom gave generously of their time to share insights into patient and staff needs as well as considerations about the design of this facility.